|

|

|

| ShellyCanton.com Biography & Tributes ● Biography

(Terra Foundation) |

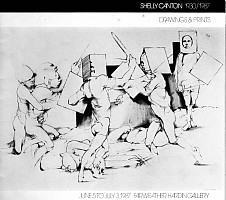

Click pamphlet: View 21 drawings & prints.

Tributes from Shelly's husband and from a noted art historian.  |

|

Biography: Terra Foundation Shelly Terman Canton was a painter, printmaker, and illustrator known for her sensitive figural works. Born Michelle Terman, daughter of a concert pianist and a businessman in Chicago, Canton began drawing as a child. She studied for a year at the University of Iowa with printmaker Mauricio Lasansky (b. 1914) before moving to New York in 1948, at the age of eighteen, to pursue a professional art career. Her illustrations were featured in Seventeen magazine and her artworks were included in exhibitions at the Downtown Gallery and Carlback Gallery, where they attracted the notice of Ben Shahn (1898-1969), the Lithuanian-born American creator of social realist paintings and prints. By 1951, however, Canton had returned to Chicago following a short-lived marriage, and with a young daughter.Canton resumed art-making after several years' hiatus. In 1956 she had solo exhibitions at Chicago's Studio 47 East and Gilman Galleries. In 1958, at the Art Institute of Chicago's annual exhibition of works by Chicago artists (held that year at Navy Pier), she won the Pauline Palmer purchase prize for her print The Meaning of Life-People, which entered the museum's collection. She had divorced and remarried, and her second husband encouraged her artistic pursuits. For the next two decades, Canton was active as an illustrator for publications ranging from Harper's Bazaar and Playboy magazines and the Chicago Tribune and Chicago Sun-Times newspapers. She showed her work widely in numerous local community exhibitions, and was represented by Feingarten Galleries in Chicago, New York, San Francisco, and Carmel, California. Canton painted in oils and casein (a milk-based water-soluble medium) and created drawings in pen-and-ink with ink washes; as a printmaker she worked in lithography, linocut, and etching. As indicated in the title of her award-winning print, the human figure was her primary subject. She frequently depicted children, mothers with their offspring, and the elderly, using a realistic but emotionally charged approach, and in her late work she incorporated elements of the fantastic and surreal to comment on issues of social injustice. In the 1960s, Canton also turned to landscape painting. Her graphic work was noticeably influenced by the spare precision and linear emphasis of Japanese woodblock prints; she also studied the works of the Old Masters on a tour of Europe and northern Africa in 1959. Although relatively little known today, Canton had realized a solid success as both a commercial and a fine artist by the time of her death at age fifty-seven. Tribute: by Harry Bouras (Collector) Shelly Canton was born with an incredible facility to draw. The long dialogue with incompetence, from which most artists salvage themselves, was bypassed by her altogether. Sadly, even before there is much of a self, the artist is encouraged to express it. For most of us that’s an easy business, because when asked to “express” ourselves we throw together the few things we’ve come to think of as our own, and are content. But not so Shelly whose catalog of doable things was as grand as ours is small. No wonder her early work was so often merely elegant and had to grow up through incomplete and sentimental subjects that seemed richer than they actually were because of her great skill. The Shelly Canton who was early on featured in Seventeen Magazine was only distantly related to the woman that she became, though the girl had a sureness no less credible than the woman. Such an artist as she was at the time could readily absorb just about anything, and thus, the work had little of that special value that comes with the image and line hard won. Great facility has been the death of a greater number of artists than incompetence. Just a little bit of study makes it clear that Cezanne bumbled in becoming the father of modern art because he didn’t have enough skill to do what he wanted to do in the first place, that is become a second rate romantic painter. The contributions of Cezanne are compensations for his inabilities. Shelly had few inabilities and could become whatever she wanted to become, long before she made the acquaintance of her later self who, “heard the whole world whispering in her ear”.What a testimony to the strength of her vision that it endured her skill. Also precocious in Shelly was her womanhood. Unfashionable as it is to even claim that such an attribute exists, it is nonetheless true that she personified womanliness and all of the embattled virtues ascribed thereto. From her earliest years she was racked by compassion and empathy, by a will and capacity to relate and understand, and, above all to feel one with all living things. I remember her description of herself as a girl arrived in New York, and how she felt because of that womanliness. Even earlier, before the age of 18, she'd escaped Mauricio Lasansky’s studio because it examined too closedly her oceanic empathy. Her recourse was always to herself, a self that was above all the woman. It is no surprise at all that she drew almost compulsively from that well of womanhood. From it that came her earliest and most tenacious “expressions”. The total image was not focused and often incomplete, but always directed in its rhetorical insistence to the well of motherhood and mirror of childhood—directions that were to be defined and synthesized into the major issues of her later work. Though, in her early work the symbols lacked resonance they were, nevertheless, alive. Such were the blessings and sources, and problems of her life...unseeming impediments that constituted at the end the foundation of her vision. What measure she had of ability and womanliness as was hers had stopped legions before, but never Shelly. The pain of her life was the unending effort to integrate them into a single statement, one where sympathy and suspicion, feeling and fear, childhood and cruelty spoke simultaneously and equally. Harry Bouras Tribute: by Irving D. Canton (husband You don’t need to know anything about Shelly to understand her art, because like her, it is candid, assertive and without guile. However, knowing something about her background can help in the appreciation of her work.She was born and raised in Chicago’s Lakeview area. Her father was a powerful figure, a businessman with a militant mission to better the world through liberal causes. Her mother was a soft, loving person, trained as a concert pianist, who thought we could better the world by reading Emerson and being nice to each other. Shelly did not wind up as some alloy of these disparate elements. They coexisted in her and were the source of her inspiration, her ambivalence, her ecstasy and her pain. From the first moment the infant Michelle (as she was named) picked up a crayon, it was evident to every-one, including herself, what her life's work would be. Her view of the world was undoubtedly influenced by the continual parade of world-class activists such as Pete Seeger, Paul Robeson, Studs Terkel and Rockwell Kent that her father's politics brought to their dining table. Endowed with enormous energy and athletic ability, she preferred to compete with the boys in sports rather than be a cheer leader on the sidelines. But, between her studies and games, every moment was filled with training herself to sketch. Her early work shows an unwavering interest in figurative line drawing rather than paint, color or abstraction. For that reason, for her first formal training, she chose to enroll at the University of Iowa, to study under Mauricio Lasansky, a renowned teacher of drawing and printmaking. But after only one year, her prodigal talent and restless nature could not be contained in a school. In 1948, at age 18, long before there were hippies, she invaded the New York art scene in tennis shoes, T shirt and jeans. The appeal of her youthful enthusiasm and the quality of the work in her battered portfolio immediately made her the protégé of the Art Directors of some major magazines. In short order, she was featured in an article in Seventeen Magazine and in two gallery shows. One of them was the Downtown Gallery, which represented Ben Shahn. He attended the opening, proclaimed her the only living threat to his work and became her mentor. Unfortunately, a short-lived marriage brought this promising beginning to an abrupt halt. After returning to Chicago, where a daughter was born in 1951, her career went into low gear. Then, in 1958, on the eve of a second marriage, she entered the Art Institute's Chicago and Vicinity Show. Her piece won the Pauline Palmer Purchase Award. With that restoration of her confidence in her talent and a new stability in her life, she surged back into work and won quick recognition in the art world via numerous shows, awards, purchases by private and corporate collectors and reproductions in magazines and art books. She worked very rapidly and rarely had to re-do a piece. Whatever she saw in her mind’s eye was swiftly and surely recreated by her strong hand. Her preference always leaned to the use of her distinctive line, and she was always searching for more interesting ways to create one, on paper, cloth, metal or acrylic, or even scratching through paint. Her subject matter oscillated without notice, as she did, from portraying her warm feelings about family, motherhood, and the innocence of children to satirizing and raging against man’s aggressive nature...between what the world ought to be and what it really was. Her later work, represented in this show, tended to concentrate on the latter. Finally, the stress of living, (as she often described it) with her “motor idling too high” wore her down, slowed her output and brought a premature end to her work and life. It is fitting to let her have the last word about who and what she was. These are two excerpts from her poems which reveal the sources of her motivation and sensitivity.

Something within me bids me, come Irving D. Canton (closing poem by Shelly Canton) Coming soon: ● A collection of Shellys annotations & stories by daughter. Many paintings explained ● Guest column will publish contributions by Ms. Canton's family & friends ● Notes from the webmaster and Shelly Canton historian, Philip Raymond | |